How To Draw Bruce From Jaws

The Jaws shark "Bruce" is ready for his closeup. Troy Harvey/Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Pic Arts and Sciences hide caption

toggle caption

Troy Harvey/Courtesy of the Academy of Move Picture Arts and Sciences

The Jaws shark "Bruce" is ready for his closeup.

Troy Harvey/Courtesy of the Academy of Picture Arts and Sciences

The first time I stuck my head into the oral cavity of a great white shark, I did not flinch. In fairness to the shark, named Bruce, he was sometime. And made of fiberglass, with chipped wooden teeth. That was nine years agone.

I found him in a Sun Valley, Calif., junk g.

A few weeks ago, I did it all again. Same shark. Just this time, I broke a sweat and closed my eyes. Bruce had gotten a makeover. He now has row after row of razor-sharp teeth and a hauntingly deep, fleshy gullet.

They're simulated, correct? Troy Harvey/Courtesy of the Academy of Moving-picture show Arts and Sciences hide caption

toggle caption

Troy Harvey/Courtesy of the Academy of Motility Picture Arts and Sciences

They're fake, right?

Troy Harvey/Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Moving-picture show Arts and Sciences

This isn't just any imitation shark. Bruce is a star: the terminal of his kind from the 1975 classic, Jaws, with a devoted fanbase and a Facebook folio. And, when the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences opens its much-predictable motion-picture show museum in Los Angeles next year, Bruce will hang in a identify of accolade.

Only when you thought it was safe to go near a museum.

The story of this fearsome 25-foot shark, his restoration, and how he made his way from picture show royalty to a junkyard and, finally, to the Academy Museum of Motion Pictures is quite a fish tale. But it's all true.

'I hope it works'

When Jaws opened in the summer of 1975, audiences weren't merely terrified by its star shark. They were fascinated. Considering the shark was, in reality, a remarkable feat of human engineering. A mechanical, man-fabricated human being-eater.

With Bruce'due south help, the movie chewed through box office records. It became the highest-grossing moving-picture show of all fourth dimension and created the tentpole template — releasing big, high-concept films in hundreds of theaters during the summer — that studios use to this solar day. Jaws was as well a disquisitional hitting, earning an Academy Award nomination for All-time Picture show and winning Oscars for its score, editing and audio. Information technology's hard to enlarge the movie's postage on 1975 America.

Greg Nicotero, now a movie effects and make-upwardly icon, remembers seeing Jaws as a 12-year-sometime, with his mother.

"My mom tried to comprehend my optics," he says of the climactic scene when the shark devours the shark-hunter Quint, played by Robert Shaw. "She didn't want me to see it considering she was afraid it would traumatize me, and it did. In a good way."

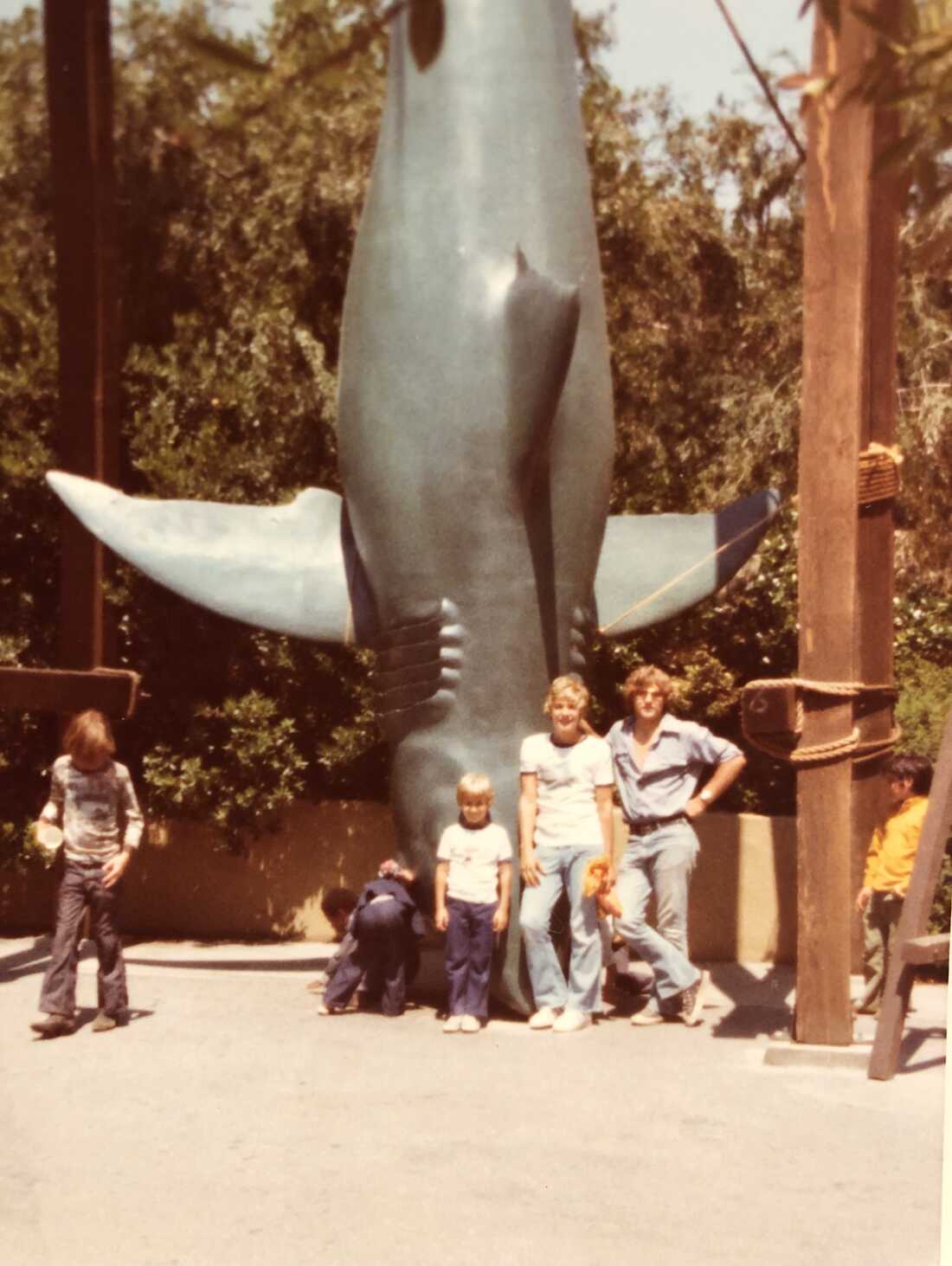

A 13-twelvemonth-old Greg Nicotero, second from right, completes his pilgrimage to Universal Studios to see the last surviving Bruce. Courtesy of Greg Nicotero hide explanation

toggle caption

Courtesy of Greg Nicotero

For young Nicotero, Jaws was a revelation.

"[It] was the movie that made me desire to do special effects, because I was fascinated that there was a agglomeration of dudes hanging out that built this."

"This" wasn't just one shark but 3, collectively nicknamed Bruce, after director Steven Spielberg'south lawyer, Bruce Ramer. And these "dudes" were a small crew of special effects craftsmen that began with production designer Joe Alves.

Spielberg and Alves had agreed: To shock audiences, the picture needed a full-size, monster shark that could swim, eat (people, of course) and survive filming in the saltwater off Martha's Vineyard. But how to build it?

Remember, at that place were no digital effects in 1975. Scares didn't come up from a computer; they were congenital in a warehouse, out of condom, plastic and wood. And, it turns out, lots of pneumatic hoses. Alves outset took the job to Universal's in-house furnishings team. Simply, he remembers, "when we talked to the effects people, they said, 'Nosotros can't practise that. It'll take a yr, year-and-a-half.' "

Alves didn't have that kind of time and turned to a special effects legend: the man behind the behemothic squid from 20,000 Leagues Under The Body of water, Bob Mattey. Alves and Mattey had no time to waste. When Jaws, the novel, became a all-time-seller, the studio rushed the film into production.

"When nosotros went to Martha'southward Vineyard, it was similar, 'I hope information technology works,' " remembers Roy Arbogast, who worked on the shark team and developed the sharks' skin.

The film's trio of homo-made sharks worked well plenty to terrify generations and break box part records. But they as well broke down and then frequently that the picture show spiraled over schedule and over budget. Studio executives were furious and feared the movie would flop.

"We were in deep trouble," Alves told me. "The studio was reluctant to brand the movie; they had no confidence in it."

And so, when filming finally ended, with no sign of the film's hereafter success, the Bruces were abandoned, Alves said. "When we came dorsum, they just dumped the sharks in the back lot, and they just rotted abroad."

The final Bruce

As a boy, Greg Nicotero was one of many fans who clamored to run into the Jaws sharks. Merely, even past the motion picture'due south release, the three original Bruces were beyond repair.

The studio had not, withal, thrown away the mold that Alves, Mattey and their effects team had used to create the Bruces. So the studio quickly made an identical 4th shark, out of fiberglass, and hung him by his tail for visitors to see at Universal Studios. The next yr, 1976, Nicotero was i of endless tourists who posed for a photograph next to this last Bruce. Little did he know their paths would cantankerous again.

Bruce hung there at Universal Studios for fifteen years, until he, like the film franchise he started, had begun to show his historic period. Around 1990, just a few years later Universal released the fourth installment, the forgettable Jaws: The Revenge, the studio cut Bruce down, bundled him with a pile of wrecked stunt cars, and shipped him off to a nearby junkyard.

Junkyard owner, Sam Adlen, did not consider the shark junk. He knew immediately what he had, and mounted Bruce onto 2 tall, metallic poles, in the heart of a small-scale clutch of palm trees. And in that location Bruce would stay, for more than two decades, menacing a sea of bit metal. One homo's individual shark.

Like Greg Nicotero, I too was enthralled with the Jaws sharks as a kid. I spent summers in the library, looking for old newspaper and magazine clippings about the Bruces. As a journalist, in 2010, I fix out to find them, or what was left.

I went straight to director Steven Spielberg.

"The original Bruce — or Bruces — were all destroyed," Spielberg's spokesman, Marvin Levy, told me back then. "And so there is no Bruce existing anywhere, nor any parts thereof."

He didn't hesitate. The Bruces, all of them, were gone.

Information technology turns out, hardly anyone, including Spielberg, knew the story of Sam Adlen and that one last, fiberglass Bruce. Just discussion had spread among the film'southward most devoted fans, that a fourth shark was out there, somewhere.

In a junkyard, fable had it.

Later on scouring the San Fernando Valley, that's where I finally found him. With the help of Sam'southward son, Nathan, I climbed a ladder and offset stuck my head inside Bruce's oral fissure. He was in terrible shape after 35 years in the California sunday. His gills were chipped, his skin croaky, his wooden teeth rotting.

But he was still, undoubtedly, Bruce. The massive dorsal. The tail as alpine equally a person.

When I reported all of this in the summer of 2010, some Jaws fans began making pilgrimages to the junkyard, hoping to catch a glimpse of the shark. Then, in 2016, when Nathan Adlen decided to close the business, he donated his father'south shark to the forthcoming Academy Museum of Movement Pictures.

There was simply one problem: Bruce was in drastic need of repair.

Bruce, meet Greg Nicotero

Greg Nicotero risks his safety to sculpt a new oral cavity for the museum-spring Bruce. Notice the regular army of zombie heads on the floor to Nicotero'due south left, awaiting use for an episode of The Walking Expressionless. Courtesy of Greg Nicotero hide caption

toggle explanation

Courtesy of Greg Nicotero

In the years since Greg Nicotero's mother covered his eyes during the terrifying climax of Jaws, her son has become 1 of Hollywood'southward become-to special effects and make-up artists and co-founded the award-winning KNB EFX Group. He is perhaps best known for his piece of work breathing life into the dead on the hitting television receiver evidence, The Walking Dead.

When Nicotero heard that the final Bruce was being donated, he eagerly reached out to the University Museum and volunteered to restore the shark.

"I remember I was kind of born to practice this," Nicotero says of the restoration.

Bruce was driven on a flat-bed to Nicotero'due south sprawling workshop in Chatsworth, Calif. For six months, Nicotero and his squad worked tirelessly.

While hanging at Universal, Bruce had been painted repeatedly. "So we peeled all that [paint] off," Nicotero says. "But and so there were a billion little stress fractures in the whole matter. And then we had to Dremel all the stress fractures out and and so patch everything. It was a mess."

To recreate Bruce's spine-tingling jaws, Nicotero and his team taped huge photos of the original sharks to the workshop'south walls and used them for reference. Nicotero sculpted new gums and a gullet while studying a blown-up still of the originals. New teeth were created using the original molds. Fifty-fifty their placement is faithful to the earlier sharks.

"I mocked up where all the teeth went using all the reference photos," Nicotero says. "How the teeth are angled — information technology'due south very specific in terms of the ones that are laying back, the ones that are pointing straight upward, the ones that are out."

And, day past day, he says, "it would go closer and closer to looking like the shark that I call up."

The last Bruce is 25 feet long and living in captivity in Nicotero's Chatsworth, Calif., studio until he makes his debut at the Academy Museum. Courtesy of Greg Nicotero hide explanation

toggle caption

Courtesy of Greg Nicotero

The last Bruce is 25 feet long and living in captivity in Nicotero's Chatsworth, Calif., studio until he makes his debut at the Academy Museum.

Courtesy of Greg Nicotero

Once finished, Greg Nicotero and the Academy Museum invited me to the workshop for a expect, before Bruce heads to the museum. Joining us were some of Bruce's oldest friends, Joe Alves, the film's production designer, and Roy Arbogast, the now-retired furnishings artist who created the original sharks' skin.

"I got goosebumps. I'g not kidding," Arbogast says after going eye-to-eye with the newly restored Bruce.

"Where's Roger? Did he hear that?" Nicotero says, practically giddy. He cranes his caput, looking for the leader of his restoration squad, Roger Baena. "Roy Arbogast has goosebumps!"

This project, Nicotero admits, was "a labor of love."

Before I peer into Bruce's mouth, and close my eyes, Arbogast and I study the old photos on the wall. In ane, I indicate to a young human being who appears to be using a heater on the shark's gums. They're wet with gum. Or saltwater. Or both.

"Is that yous?" I inquire.

"That's me," Arbogast says, shaking his head. "I'll be darned. That's me. I was such a young, handsome guy so." He laughs.

Jeffrey Kramer, Greg Nicotero, Bruce the Shark, Roger Baena, author Dennis Prince, Joe Alves and Roy Arbogast. Troy Harvey/Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences hide caption

toggle caption

Troy Harvey/Courtesy of the Academy of Motion Motion-picture show Arts and Sciences

Jeffrey Kramer, Greg Nicotero, Bruce the Shark, Roger Baena, author Dennis Prince, Joe Alves and Roy Arbogast.

Troy Harvey/Courtesy of the University of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences

Actor Jeffrey Kramer as well drops by. He played the deputy to Roy Scheider'south police primary in Jaws and Jaws ii. Kramer remembers product began with him discovering the remains of the shark's first victim on the beach.

"I was so nervous I could have thrown upwardly on the beach," Kramer says. "But what an experience. I mean, who knew, Joe?"

Kramer looks at Alves, and then Arbogast. They all stare quietly at the shark that, after more than four decades, suddenly — in one case again — looks like those sharks of 1974, when these men were all much younger, their careers withal alee of them.

Before production brutal behind schedule and the budget doubled.

Before the famous music.

Before the blockbuster.

"Who knew?" Kramer says, wistfully. "Who knew?"

Source: https://www.npr.org/2019/08/09/745651910/jaws-shark-gets-his-bite-back-a-love-story

Posted by: gordonopoetinat1997.blogspot.com

0 Response to "How To Draw Bruce From Jaws"

Post a Comment